By Ruchira Talukdar

The Adani Group’s Carmichael coal mine in the Galilee Basin in Central Queensland has been in the news largely for the wrong reasons.

As the largest proposed Australian coal mine, as well as one of the world’s largest, the Carmichael mine first made major headlines in July 2014 when the Abbott-led federal government approved the mine with “strict environmental conditions”.

At the core of billionaire Gautam Adani’s $16.5 billion Australian investment lies a proposal to dig six open cut coal mines and five underground coal mines in the semi-arid Galilee Basin spanning 28000 hectares (seven times the area of Sydney Harbour), build a railway line from the coal pits to the coast, and expand the Abbot Point coal port adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef to include a new terminal. The company estimates to extract and ship 60 million tonnes of black coal to India each year. The mine is expected to yield coal for ninety years, providing electricity for ten million Indians for hundred years.

When the former Newman government in Queensland approved the mine and federal Environmental Minister Greg Hunt issued a final approval, two clashing sets of news stories – one supporting its economics under a moral guise and the other dissecting the environmental impacts, broke out across the national and international media.

Impacts

For the mine-opponents, the list of concerns ran long:

- It will drain twelve billion litres of water annually from local rivers and aquifers, leading to a one meter drop in the local water table

- The location and construction of the coal port at the edge of Great Barrier Reef will:

- risk marine animals found at the location like humpback whales, snubfin dolphins, dugongs and rare sea turtles.

- dredge the sea bed inside the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage area disturbing sea grass meadows and the Reef’s ecosystem.

- threaten the Caley Valley Wetlands, home to 41,000 waterbirds and an important turtle nesting beach, which is most likely location for the onshore dumping of 1.1 million cubic metres of dredge spoil

- Burning of Carmichael coal will produce emissions – an average 79m tonnes of carbon a year – greater than that of New York city, and take up 5% of the world’s remaining carbon budget having regard to the 2 degrees centigrade warming limit

- Over 20,000 hectares of native bushland will have to be cleared, pushing the largest known population of the endangered Southern Black Throated Finch towards extinction

- The company’s bleak history of environmental performance in India – including bribery, theft and illegal export, destroying a designated conservation area and disrupting ecosystem based livelihoods – does not inspire confidence.

Approval process

The battle between economic and environmental interests over Australia’s largest proposed coal mine has only intensified over the course of the last two years. But this battle is not evenly pitched any more as the timeline below indicates, with its financial viability waning, and environmental and social concerns gathering a storm of public support and holding the project ransom through court challenges:

|

March 2014 |

Two local conservation groups bring two separate legal cases against Adani’s proposal to dump dredge spoils in the Great Barrier Reef zone. The company later withdraws this proposal.

|

|

May 2014 |

Queensland Government approves the Carmichael coal mine despite concerns of the Independent Expert Scientific Committee assessing the project’s impact on water resources.

|

|

July 2014 |

Federal Environment Minister Greg Hunt approves the coal mine with 36 strict environmental conditions. Environmental groups, scientists and the Australian Greens say a mine with an impact of this scale should never have been approved.

|

|

Oct 2014 |

Indian environmentalist Debi Goenka from Conservation Action Network (CAT) submits at a hearing in the Land Court of Queensland that “the coal from Carmichael, when burnt in India, threatens the health and livelihoods of rural poor in India…neither can these people afford the electricity that will be generated.”

|

|

Nov 2014 |

The company signs a memorandum of understanding with the State Bank of India for a loan of up to $1 billion to help fund the Carmichael project. The announcement is made in Brisbane where Gautam Adani is accompanying Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the G20 summit. The news causes controversy in India; the deal is said to provide further evidence of Modi and Adani’s proximity. The agreement is quietly withdrawn by the State Bank of India in 2015.

|

|

November 2014 |

The Newman Government in Queensland, which declared itself to be in the business of coal, pledges $450 million in subsidy for the railway line in a bid to kick-start the expansion of coal exports. Documents released under the state’s freedom-of-information laws have shown that treasury officials warned the Newman government about the financial unviability of the Carmichael project. |

|

February 2015 |

In what is described as a seismic Queensland election, the Liberal National Party is defeated by Labor. Widespread corruption, poor governance and the reckless push for coal exports are said to have contributed to the right wing government’s defeat. The new Premiere promises to scrap taxpayer subsidies for Adani’s coal project.

|

|

March 2015 |

A local conservation group challenges the decision to dump dredge spoil onshore at the Caley Valley Wetlands in court.

|

|

May 2015 |

The Wangan and Jagalingou people, the traditional owners of the land, launch a federal court case against the Carmichael project; clan members ask international funders to withdraw support. They are concerned that Adani “grossly overestimated” the economic benefits in taxes and jobs to Queensland.

|

| June 2015

August 2015

|

Adani suspends two major contractors including Korean construction company Posco, raising speculations about the company’s ability to finance the project.

The Federal Court asks Environment Minister Greg Hunt to remake the Carmichael decision. The locally based Mackay Conservation Group had earlier challenged the mine’s impacts on two native species classified as vulnerable – the Yakka Skink and the Ornamental Snake. The court asks Minister Hunt to take this conservation advice into account. |

|

Aug-Sep 2015 |

The Commonwealth Bank and National Australian Bank, two of Australia’s largest lenders to resources projects, pull out of financing the Carmichael project. Eleven high profile international financial institutions had already withdrawn from the project by this time due to a combination of falling coal prices and the environmental impacts of the coal mine amply highlighted by activist groups.

|

|

Oct 2015

|

Minister Greg Hunt approves the Carmichael coal mine for the second time.

|

|

Nov 2015 |

A national environmental group challenges the second federal approval for Carmichael on the grounds that it is against Australia’s obligation to protect the World Heritage listed Great Barrier Reef. A hearing date has not yet been set.

|

|

Dec 2015 |

In a backroom meeting with the new Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Gautam Adani asks for legislation to prohibit activist groups from going to court over technical errors in the approval process (seeking judicial review).

|

|

Dec 2015 |

The Land Court of Queensland advises that the Carmichael mine should be granted a mining lease and environmental licence needed for its operations. Based on a local group’s objections, the licences had been subjected to a court hearing and consequently delayed.

|

Image source: http://reefdefenders.net

Dirty coal

The simple truth is that like the Keystone XL pipeline which was built to carry crude oil from the tar sands in Alberta, Canada all the way to Texas, Carmichael has attracted the world’s attention in a vulgar manner at a time when anti-fossil fuel activism has started making an impact.

Canadian journalist Naomi Klein’s latest book This Changes Everything shines the critical spotlight on capitalism’s role in perpetuating fossil fuel driven climate change, and singles out some of the world’s largest oil, gas and coal extraction projects as anti-people and anti-planet. Enumerating several racially and geographically diverse grass roots campaigns under the global mass movement Blockadia, This Changes Everything makes as much of a case for justice for environmental refugees, first nation people and followers of ecosystem-based livelihoods as for limiting the global rise in temperatures under 2 degrees.

Coal has become synonymous with dirty and dangerous. A global fossil fuel divestment campaign has seized the opportunity of falling coal prices due to a slowdown in demand from the largest buyers – China, India and the United States – to ebb the flow of global capital to large new coal mines. In Australia, environmental groups, scientists, prominent Australians and the Green Party have publicly called for a ban on any new coal mines.

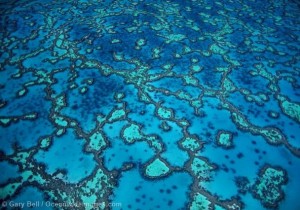

Saving wonderland

The other compelling force against Gautam Adani’s Australian ambitions is the Great Barrier Reef, planet earth’s blue wonderland, so big that it can be seen from outer space. Five times the size of Tasmania, the Great Barrier Reef stretches 2300 kilometers along the coast of Northern Queensland and contains 2900 different reefs, 1500 species of fish, four hundred varieties of hard corals, one third of the world’s soft corals, 134 species of sharks and rays, six species of threatened marine turtles, more than thirty species of mammals, over 3000 molluscs, thousand different sponges, 630 species of starfish and sea urchins, and 216 bird species.

The mind-boggling diversity of life-forms and the vast expanse of the Reef constitute the identity of many aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and in the present day support a $6 billion tourism industry and 63,000 livelihoods.

But the Reef is in grave danger; half of its coral cover has been lost since the mid 1980s, and climate change, resulting in warmer and acidic oceans, increased storms and sea level is the single biggest threat to its future. At the current level of global warming, the Reef is at risk of shrinking to one tenth of its size by mid-century.

The life and death condition of the country’s most iconic asset has radicalised Australian environmentalism. Scientists have called for all new coalmining and coal exports from Queensland to be scrapped to avoid their impacts on the vulnerable Reef. Environmental and civil society groups of all shapes and sizes have united under one banner to fight for Australia’s climate and the Great Barrier Reef. Backed by growing voter-constituency support, this mass movement is challenging the very basis of Australia’s economic wealth, a significant portion of which comes from the mining and export of natural resources.

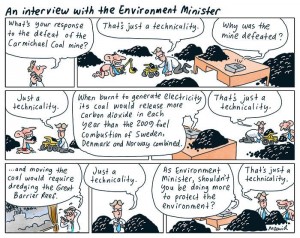

Cartoon by Mark David @mdavidcartoons

Snakes and ladders

Attempting a gigantic coal project at the brink of the precious Reef at this crossroad in Australia’s environmental movement would have invariably met with a tsunami of resistance.

Like a never ending game of snakes and ladders, this movement snared the Carmichael mine in ceaseless “lawfare” despite attempts (albeit unsuccessful) by a supportive Federal Government to weaken Australia’s environmental laws to prevent activism against the fossil fuel sector.

While groups with expertise in marine ecology stopped Minister Hunt from allowing a proposal to dump dredge spoils in the waters of the Barrier Reef, another collective geared up to prevent the alternate proposal to dump dredge spoils onshore.

When collective action to stop the expansion of the Abbott Point coal terminal proved unsuccessful, the battle shifted to the actual mine site in the semi-arid Galilee Basin. Unusual alliances of green groups and farmers who otherwise disagree on climate change united to fight a common enemy in court. Their concerns focussed on destruction of water sources and extinction of native species.

Resistance to the Carmichael coal mine acquired similar overtones to the high profile Keystone blockade when traditional owners took court action against its approval which they said would “tear the heart out of the country”.

All along, an anti-coal global alliance worked to undermine funding for the project on the basis that Carmichael coal burning will make too hefty a withdrawal from the world’s remaining carbon budget.

The latest blow to the coal mine was delivered in November 2015 through a court case brought by the national environmental group Australian Conservation Foundation which challenged Minister Hunt’s second federal approval. The challenge made the serious and high profile allegation that approving the Carmichael project was inconsistent with fulfilling Australia’s World Heritage obligations towards the Great Barrier Reef.

As the pioneering venture in the Galilee Basin – a 250,000 square kilometre area, slightly bigger than the United Kingdom that is estimated to hold over 27 billion tonnes of coal – the Carmichael project can have a multiplier effect. Adani’s rail and port infrastructure can bring to life five other proposed megamines including that of Indian company GVK. The Foundation has explicitly stated that it is committed to stopping the megamine in its tracks, not merely delaying it.

Despite the Federal Government helping out by approving the project twice as well as expounding the clichéd argument that coal will lift India’s rural poor out of poverty, and regardless of the Queensland government bending over backwards by subsiding the rail project, the snakes in the approval game for Carmichael outdid the ladders. The future of the project and that of the entire Galilee Basin now hangs on the fate of the latest challenge even as market conditions grow more unfavourable with every passing day.

It must have been with a high level of frustration that Gautam Adani (reportedly) told Prime Minister Turnbull “…Some technical mistake here and there and they go to court…Now it is enough…In OECD countries, you are not given approvals with closed eyes.”

The laws involved in the approval process for the Carmichael mine, as in the case of any major project, have proven a weapon for green groups and a thorn in the flesh of Adani’s Australian ambitions.

On the one hand environmentalists argue that if Australia’s national environmental laws – the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) – were strong enough, a project with the harmful potential of Carmichael would not have been approved in the first place. And yet, these same legal procedures free of political manoeuvring and a (relatively) accountable system of governance has enabled civil society to stall the Carmichael project.

The undermining of Gautam Adani’s Australian ambitions through green tape and green activism is seriously ironic because his private wealth in India has been amassed through consistent violation of such institutions and agencies.

Ram Surat Yadav at Mundra port in India, funded by Gautam Adani. Photo: Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/concerns-at-barrier-reef-contractors-humanitarian-environment-record-20140904-10cgxk.html#ixzz3yjKwcLRJ

Backstory

The Adani Group is India’s largest private trader in coal and also the country’s biggest private port operator. The scene of the company’s most telling environmental offences is at the location of its crown jewel investment – a port and special economic zone (SEZ) at Mundra in the Gulf of Kutch in Gujarat.

Behind the industrialist’s astounding rise to wealth within one generation – from a commodity trader in 1998 he is now one of the ten richest Indians with a personal net worth of $2.65 billion – lies a friendship with Prime Minister Narendra Modi which has yielded rich business dividends while destroying the ecological balance and livelihoods in the region:

- The company acquired land at throwaway prices from the Gujarat Government under Modi for its port and special economic zone; Adani then sold significant portions of this land to other companies at hundreds of times the cost value

- Illegal mass clearing and destruction of mangroves inside a conservation area at the site of the Mundra port has thrown the ecological balance of the region out of gear; mangroves prevent erosion and regulate salinity, apart from supporting estuarine and tidal species.

- Dredging at the port site and discharge of inadequately treated waste water has damaged mudflats, creeks and the estuarine area; fish stocks have plummeted disrupting the livelihoods of fishing communities

- The special economic zone was built before acquiring environmental approval from the Centre even as the Modi-led Gujarat government looked the other way.

- The list of violations and non-compliance at the Mundra port and SEZ ran so long that a special committee chaired by environmentalist Sunita Narain was set up under the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF) to investigate the crimes. The committee found that the company circumvented statutory processes by using different agencies at the Centre and state for obtaining clearances for the same project. It also bypassed the public hearing procedure, critical for addressing the concerns of locals, on one pretext or another.

- The Gujarat High Court declared the special economic zone illegal in early 2014 and referred the matter to the UPA government at the Centre for a belated clearance if applicable. The company maintained that it did not violate any rules. A decision was left pending while national elections were called, and no sooner did Narendra Modi become prime minister than the SEZ was cleared for operations.

- Outside Gujarat, a major scandal was brought to light through a Karnataka Lokayukta investigation which found the company involved in theft and illegal export of iron ore

Gautam Adani, India’s self made billionaire, a veritable juggernaut, has dreamt big and his ambitious projects in India have seldom failed. This is partly due to the impunity with which he has disregarded or violated environmental procedures while receiving unprecedented political favours in Gujarat. The question now is, can he replicate this success in Australia?

The final equation

The Carmichael project is the biggest overseas venture by an Indian industrialist. It is vertical integration (a model Adani has followed in India) magnified ten times over – Adani will mine the coal in Galilee Basin, transport it on his own railway line to a port in Abbot Point that he owns, and then ship it to his own Indian port from where it will be taken to his own power plants. Neither Australia nor India has seen anything on this scale before.

But winds of change are blowing around the world. The cost of solar energy has fallen to as low as that of coal, helping boost demand for clean energy. After President Obama’s rejection of the Keystone pipeline project and the Paris Climate summit’s resolve to keep global warming at 1.5 degrees centigrade, all eyes are on Australia and the giant Indian coal mine at the edge of the Great Barrier Reef. After the Paris summit China announced a moratorium on new coal mines, and President Obama banned new coal mines on public land which accounts for 40% of America’s coal production for three years.

With the Carmichael project having lost significant financial ground, and Australia at risk of international disrepute over a bad decision for the Great Barrier Reef, the mine’s approval is not merely an environmental concern. It is a high profile diplomatic issue for the Turnbull Government.

If the forces of change outweigh global capitalism’s appetite for coal, the mine will be stopped in its tracks, as the latest litigant resolves do to. In the event that Carmichael does not survive the court challenge, the very laws and agencies Gautam Adani flagrantly flouted in India will prove to be his undoing in Australia. To those affected by Adani’s legacy of environmental abuse in India, such an event might bring a measure of justice, belated and vicarious, but nevertheless needed.

Ruchira Talukdar, an English (Hons) graduate from Lady Shri Ram College, New Delhi, made a conscious commitment towards environmental conservation ten years ago. As Communications Strategist at Greenpeace, the global environmental organisation spread across fifty countries and later as Environmental Campaigner at Australia’s longest serving conservation group, the Australian Conservation Foundation, Ruchira has been involved with diverse challenges including tackling climate change, resisting genetically modified (GM) food crops, combating Japanese whaling in the Southern Ocean, restoration of Australia’s largest river the Murray-Darling, and strengthening Australia’s national environmental laws. Ruchira also holds a Masters Degree in Environmental Studies from Melbourne University.

Disclosure: The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and not of her former employer, the Australian Conservation Foundation.

Featured image source: http://reefdefenders.net

The ACF challenge of the approval decision will be heard in the Federal Court in Brisbane on 3rd and 4th May.

Thanks Stu, that must have been announced very recently?