By Anupama Pilbrow

When I was ten years old, my godsister’s Indian mother and non-Indian father gave me a children’s novel called Neela: Victory Song by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. I devoured it. It was about a girl my age living through India’s Partition. Neela was the first book by an Indian author that I ever read to myself.

I remember reading Divakaruni’s novel like it was the first of many small steps across the Rubicon. In the same way, I remember reading Salman Rushdie for the first time, I remember reading Vikram Chandra for the first time, Kiran Desai, Toru Dutt, Rabindranath Tagore, Aravind Adiga, Kamala Das, Sarojini Naidu, Nissim Ezekiel. These writers represent my history and my self. Not in the way that I love them all (I don’t), but in the way that their writing informs mine. And I know it does because I call on it. Their influence is strong.

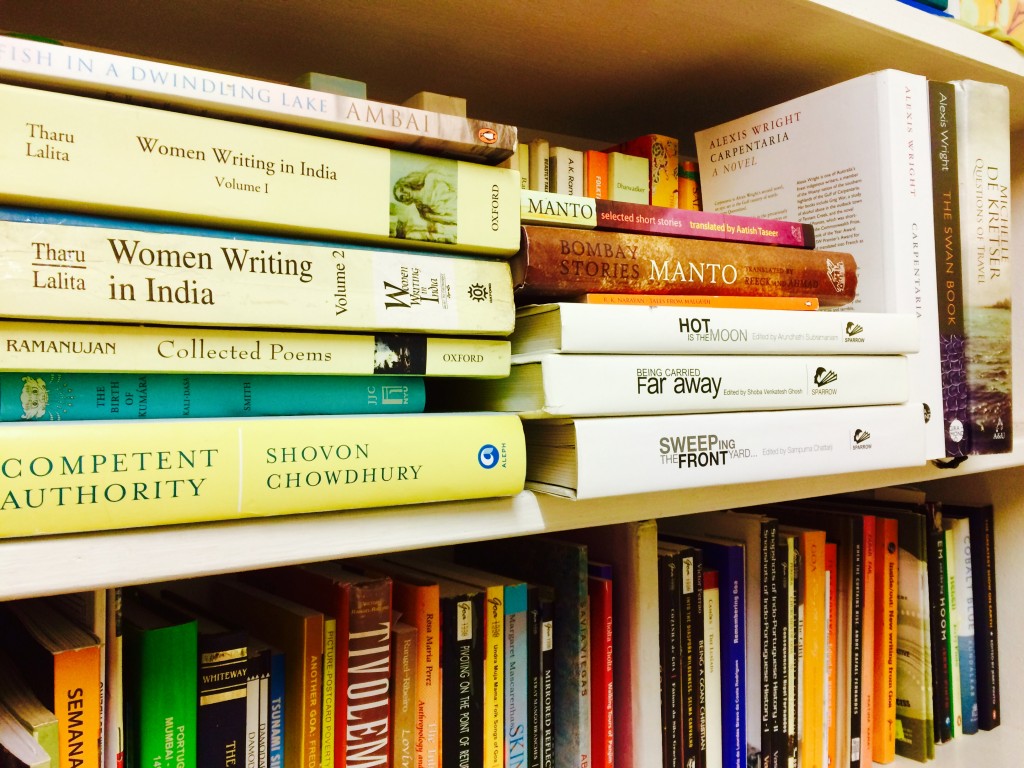

Now, I’ve read books by non-Western and Western writers. But, I obsess over and seek out the non-Western names on bookshelves. I talk about the non-Western writers. I will not be a passive voice in this homogenous English-language literary culture.

Talking about literary influence is important. We know that all new writing is filtered through the potluck pool of old or extant writing. Beyond offering respect to existing writers, though, it is helpful and important to tease out literary influences in order to mine and explore the depth and nuance that comes from literary and historical context. No vein of literature is isolated from any other.

Last year, after finishing The Inheritance of Loss, I found and read a conversation between Kiran Desai and her mother Anita Desai in which both discuss in part their literary influences. Anita says she had been almost overpoweringly influenced by English author Virginia Woolf, had used her “as a kind of tuning fork”. Meanwhile, both speak of the shifting legacy of Indian writing in English, how “astonishing that now a whole generation has grown up reading Indian literature in English [when, in Anita’s time as a student, they] read no Indian writers at all.”

The honesty and brutality of this statement is striking, especially considering the culture of literary exchange that has evolved in only the last 50-60 years.

I’ll give an example that’s close to home in order to illustrate the evolution of this exchange. I’ve chosen it for clarity and conciseness, and not to single out one Australian writer above any others.

In an interview with Pradeep Trikha, Sydney-based poet and founder of Mascara Lit Review, Michelle Cahill lists a few of her influences. She names Eliot, Plath, Judith Wright and Robert Adamson, and she specifically names Indian writers Sujata Bhatt, Jeet Thayil, Ravi Shankar, Tagore, Arundhati Subramaniam and more. I love lists such as these—they begin to explicitly map literary genealogy by revealing the correspondences and commonalities between writers. Lists like these say, “Go, read!” They also say, “This is how you read.”

However, it is crucial to note that such lists are always incomplete. There isn’t, and never could be, of course, a comprehensive list of a given writer’s specific influences.

In the context of the Australian literary community, a list like Cahill’s makes intuitive sense. Australia is right next door to Asia, there are many Asian-Australian writers, and there is a history of cultural exchange between the two continents. However, as in Anita Desai’s case, or, for more home-grown examples, in Nam Le’s case (“Grahame Greene’s one of my favorite authors”), or Dominic Golding’s case (growing up reading “Enid Blyton to Rudyard Kipling”), or Alice Pung’s case (she lists some influential authors; Robert Cormier and Cynthia Voight), paying homage, or taking influence from non-Western and specifically Asian writers is not a given.

Why are these correspondences so imbalanced? Western and non-Western writing has been commingled throughout history, after all. One should expect that literary influence be representative of various literary traditions besides the Western. Poetry and the novel are not European inventions.

Well, for one, you might say that non-Western writing does not receive nearly as much hype or recognition and, as a result, is not so famous or compelling. Hold on, though. Here’s a counterexample; even Ezra Pound was enamored of and influenced by Tagore.

I think it’s more complicated. Western writing overpowers other writings because it takes great effort to step outside the Western literary paradigm—even for writers and readers in a continent like Australia, which is geographically and intellectually close to Asia. Shifting this paradigm takes conscious work—work like asking Australian writers to name their Asian literary influences. Work like obsessively talking about Asian authors.

Change is coming; Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger is being added to VCE English reading lists as, among other things, a reflection of the “cultural diversity of the Victorian community.” This is a powerful first step because it ensures that South Asian literature is being read not just by those with a South Asian background.

Prescriptive reading lists that account for cultural diversity necessarily perforate insular and exclusive reading habits. I can only hope that students exposed to Adiga’s novel will be more willing to bring up his influence in their subsequent reading. Recognition and consumption of diverse literary paradigms shouldn’t be left to chance, or the coincidence of one’s birth and heritage.

I am still waiting for it to happen that writers are asked also to bow to the Orient, the East, the literary ‘outcasts’ and the ‘so-far-unnamed’. Representation of diversity is a goal worth pursuing, in any and all fields. As elsewhere, it is vital also in the context of literary genealogies. In Australia, and elsewhere, a good first step is to answer the question, “Which Asian and South Asian writers do you like?”

Anupama Pilbrow studies mathematics at The University of Melbourne. She works as deputy editor of The Suburban Review and co-manager of Sibboleth Poetry Reading Group. She received the 2016 Dinny O’Hearn Fellowship for her poetry manuscript the ravage space, a work dealing with Asian diasporic experience in Australia. Her work has been published in local and international poetry journals. She lives in Coburg.