By Prakash Subedi

To be a non-white writer in the west today is probably very different from it was, say, fifty years ago. Books and ideas travel much faster now, and even if you are writing and publishing in the west, there are more and more people back home who have access to your works. And while this was always the case to some extent, it is now truer than ever that the most passionate responses and vociferous objections to your work are likely to come from readers at home. More often than not, by virtue of being based in a western country and writing about your home, your writing is treated with wariness and your motives with suspicion.

With few writers of international fame writing in English, and a smaller readership at home, Nepal’s case might be a little different from other South Asian nations. Samrat Upadhyay and Manjushree Thapa, the two best-known Nepali writers writing in English, command a less numerous as well as a different kind of readership than say Salman Rushdie or Arundhati Roy. Their writings, even when published by western publishing houses, find a larger and much more engaged readership at home.

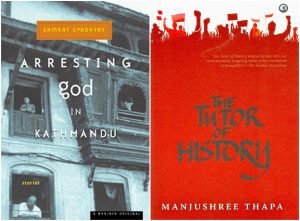

Samrat Upadhyay’s Arresting God in Kathmandu (2001) was the first English book of fiction by a Nepali writer to be published by a western publisher (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, US). The book not only garnered instantaneous fame in Nepal but also faced a lot of criticism, especially for the way it allegedly highlighted the negative side of Kathmandu, projecting it as a poor, corrupt and dirty city rampant with sexual promiscuity. Upadhyay became an overnight celebrity in Nepal, but readers questioned whether, while he was treated with indulgence in Nepal, he had any real international recognition. Manjushree Thapa, another well-known Nepali writer writing in English, has faced similar treatment: while she is hugely admired, her representativeness and authenticity are often questioned. As the two most well known Nepali writers living in the west (Upadhyay lives in US, Thapa in Canada) and writing in English, each of their works becomes not only the instant talk of the town but also the recipient of sometimes vicious criticism, quite often for ‘extra-textual reasons.’

There is an interesting double standard at work in their reception at home. While many writers have written about poverty, corruption and sex in their works of fiction in Nepali, they have rarely been criticized for doing so and in fact writers are expected to write about issues that society shies away from.But this expectation gets turned on its head when the writer lives away from home and is courted by international publishers. The criticism, if any, isn’t as harsh when the writers are based in Nepal: Sushma Joshi’s End of the World (Fine Print, 2008), Rabi Thapa’s Nothing to Declare (Penguin, 2011), Prawin Adhikari’s The Vanishing Act (Rupa, 2014), and Pranaya Rana’s City of Dreams (Rupa, 2015), all expose murky aspects of Kathmandu/Nepal, but they have rarely been criticized in the same manner as Upadhyay or Thapa.

Is it because we don’t want ‘outsiders’ to know about our dark side because that hurts our ego? Or is it that we resent the writers for capitalizing on our suffering for what we think of as their personal gain, without necessarily sharing in it by staying in Nepal? Or is it simply a version of the tall-poppy syndrome, as prominent a cultural phenomenon in Nepal as elsewhere. Thus, for writers from Nepal, at least from the perspective of readers back home, it is not so much having “cultural cache” but having your perspectives treated with suspicion that becomes a bigger problem, especially since, as far as I can tell, they want to write about Nepal and its cultural specificity because that is what they feel closest to.

In response to the charge that Midnight’s Children portrayed an inauthentic picture of India Rushdie writes in “Imaginary Homelands,” that writers in his position, “exiles or emigrants or expatriates,” are haunted by some sense of loss and in their urge to come to terms with this loss “create fictions, not actual cities or villages, but invisible ones, imaginary homelands, Indias of the mind.” Yet no reader will be content with the thought that it is a “[insert country] of the mind” that is being presented to her/him, and not a ‘real’ place. For readers at home, fictional representations constitute a misrepresentation or a partial representation of home, while for readers elsewhere it is ‘information’ about a foreign country and culture. Neither is entirely willing to take a work of fiction seriously for its imaginative and poetic force, and not its portrayal of an actual place. If this were the case the discussion might be focused on the writing and not the writer.

As things stand, almost all the non-white writers writing in English, and especially those based in the west, feel this discomfort: western readers expect them to tell ‘exotic’ stories, whereas their readers back home disparage them for this very ‘exoticization.’ To be a non-white writer in the white literary world is to be a living dilemma. You are expected to write in English with native command, yet without that native ‘sound,’ otherwise what’s the point of a non-white writer. Similarly, you are supposed to write about a world you don’t live in anymore because the world you inhabit now is not really your world, and therefore your subject. Moreover, there is a general tendency among ‘metropolitan’ readers to read white writers more for style (and content) and non-white writers for content (or, an ‘exotic’ style).

As a non-white writer writing in the west, then, you probably are expected to write about the unfamiliar, the strange, yet in a language and style that doesn’t sound too unfamiliar. This is a terrain where you can’t be who you are and should try to be who you probably aren’t anymore. And, the moment you don’t sound strange anymore and your style and diction sounds too familiar, you have lost that fertile ground of conflicting identities, languages, cultures and realities, and probably lost a chunk of your readers who ironically like you for being conflicted and unsure. Do we even think of someone like Rushdie when we think of a non-white writer anymore? And, should we consider that as an achievement on his part or the ultimate failure?

A non-white writer, thus, faces constant pressure, a simultaneous push and pull, while trying to please two otherwise diverse and contrasting audiences at the same time. And, even when you are writing in English, you have to give proof of your distinctive culture, on the one hand, and not have your writing fall into that category of writing that has already been stereotyped as South Asian, on the other.

So, if you are a Nepali writer living in Australia and writing in English, for instance, you are supposed to do these three things (some for your publisher’s/readers’ sake, and some for your own): first, tell a Nepali story for the Australian/western audience; second, don’t offend your Nepali readers back home by the story you told to ‘outsiders’; and, third, sound Nepali/South Asian through your content and style, without sounding clichéd.

Quite a tall order!

Prakash Subedi is a Nepali writer and translator. He has published two volumes of poetry, Stars and Fireflies and Six Strings (a co-authored anthology), and a number essays, critical writings, translations and reviews. He has served as an editor of the journals Of Nepalese Clay, Literary Studies and Devkota Studies. He is currently working on his PhD in Literary and Cultural Studies at Monash University.

Nepal Literature Festival, Pokhara, image : Bhim Ghimire