By Jasmeet Kaur Sahi

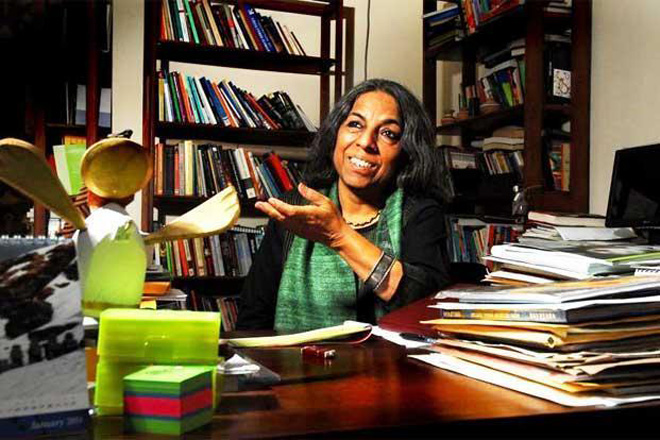

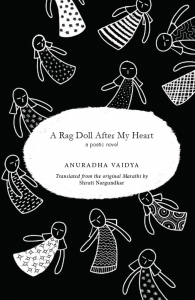

In July last year, noted Indian feminist publisher, writer and activist Urvashi Butalia was in Melbourne for the launch of A Rag Doll After My Heart, a poetic novella translated from the original Marathi into English by Melbourne-based writer and educator Shruti Nargundkar. The launch was held at the Australia India Institute in Melbourne.

Butalia along with her friend Ritu Menon established India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women in 1984 and ran it successfully for nearly two decades. In 2003 they parted ways, and Butalia set up Zubaan Books, an imprint of Kali for Women. Zubaan published A Rag Doll After My Heart.

At the launch, Butalia spoke of her many roles in publishing: as a writer, an editor, a translator, as well as a publisher. She said that India is a multilingual country and Indians are always translating within their languages and different registers. She said, “Translation is an act of daily negotiation, sometimes within the same city and within the same language.” What she implied was that sometimes this has nothing to do with not understanding what the other is saying; this difference can simply happen because of a difference of gender, class, caste, and so on.

She said, “In India, language is classed: upper class & upper caste speak a certain register, working-class speaks in another one, and quite often the “untouchables” reject these registers and take up English to subvert the supposed hierarchy of language.”

Butalia, who is in the process of chronicling the life of a transgender person in Delhi also said that the transgender community speak in a language that utilizes the plural in terms of personal pronouns (like the Indian royals of yesteryears would have). She said this is a strategy that helps in not being able to tell a transgender person’s gender.

English is still the main language of publishing in India. Butalia said that the government of India has tried to impose Hindi as a national language for a long time, but the reality of the situation is that India has 22 languages and so as a legacy of the British rule of India, English has become a sort of pan-Indian language, even though it is spoken by only 6-7% of the population. English, which is a language of power and privilege in India, is also the language in which Zubaan largely publishes, and Butalia acknowledged that by publishing in English, publishers remain in their comfort zone. She said that the fact that Kali always published feminist works gave the publishing house enough political mileage, and that it was being done in English gave the works a place of privilege.

But the real challenge for publishing houses in India is finding rich stories in different languages in India. She said that bringing out stories of those women in India who do not have agency, in terms of money or means or even language is a big challenge and opportunity because the language women use in India is very different from the language men speak, which is mainstream or “malestream” as she called it.

An interesting notion about language that Butalia highlighted was the loss of the ‘writing language’ as a result of migration. She mentioned this in connection with the book, A Life Less Ordinary by Baby Halder. It is the story of Halder, a domestic worker who migrated from West Bengal to Delhi in search of work. Halder wrote this book in her native Bengali. Her employer, a university professor, translated her book into Hindi. Haldar, who achieved success through her writing, as a result then became un-publishable as a Bengali writer, even though she wrote in her native Bengali. The reason given by publishers for this was that her migrating to Delhi had ‘Hindi-ised’ her Bengali.

Before the launch, I had the privilege of sitting down with Urvashi Butalia and Shruti Nargundakar for an hour-long chat. They spoke about their craft, their writing process, the challenges of setting up a feminist publishing house, translation and women’s publishing in India.

Abandoning a Fulbright

Jasmeet Kaur Sahi (JKS): Why a feminist publishing house in 1984? I know the simple answer can be ‘why not?’ but what I want to really ask is why then and why feminist?

Urvashi Butalia (UB): The early 80s in India was the time when the women’s movement, or the new women’s movement was very strong and raising up many issues, taking up a whole lot of questions. I was quite involved in that movement, so we were very pre-occupied with violence against women, with issues of dowry, marriage laws and so on.

And whenever we wanted to try and understand the shape that things had taken — for example questions like was dowry a relatively new urban phenomenon, was it limited to North India, was it only Hindu, why was there so much violence involved, we looked around for things to read and there was absolutely nothing. Except the occasional book written by a western scholar who might have had a chance to come to India for a few months and written the definitive book on it, which you had to buy back at expensive prices.

So, as an activist in the movement I was very frustrated at the lack of knowledge around us about women by women. I happened to be working at Oxford University Press (OUP) at the time. But it also frustrated me that inside my publishing house, there was no awareness of this great lack that I was seeing in my political life.

I tried to persuade my bosses – who were all really nice guys, not particularly chauvinist – but they didn’t think there was anything in it. Questions that arose were ~ will women write; the issues that women write about, are they serious enough; is there a market; where will you find the writers and they dismissed it. So I thought: well if they are not interested, I’ll have to do it myself and I was young and foolhardy and I thought, ‘Yeah, I can do it’.

By the time I took that that decision I had been working in publishing for six years, which is not enough to start your own publishing house. I had since then left publishing and started teaching publishing while continuing with OUP in a freelance capacity, when I got a bit derailed. I won a Fulbright fellowship and when you are 30 and you get a Fulbright, you take it. And there I was: on my way to Hawaii for a PhD thinking what I really want to do is set up this publishing house. On my way, I stopped in London to spend time with friends and to visit a publishing house that I knew well, called Zed Books who were publishing books on what was then called the Third World. My friends there said, “Oh! So if this is your dream then why are you going to Hawaii?” They asked me to stay back because they wanted to set up a women’s list, saying, “Do it for us and then go home and set up your publishing house”.

And so I abandoned the fellowship, stayed on in England for two years with Zed and during that time made all the plans, came back home and set it up.

The history of The History of Doing

JKS: So, how did you pick your manuscripts for publishing: Were you authoring them, anthologizing or commissioning work? What was the process of setting up an independent publishing house at that time?

UB: When I came back to India after working with Zed, a friend of mine, Ritu Menon joined me and the two of us effectively did the setting up together. We were very clear right from the beginning that we would not publish our own stuff, even though we had things to say. So we looked around for manuscripts, and we had in our heads certain areas that we wanted to publish in. For example, we were very clear that one of our first books should be a history of the Indian women’s movement and this book took 9 years to materialise and went on to become our perennial classics, which gets reprinted every year, it’s called The History of Doing: an illustrated account of women’s movements in India.

We wanted to publish both fiction and nonfiction and we wanted to translate from the Indian languages. Since we were so connected to the women’s movement, we went to our activist friends and asked them what they were thinking, we attended seminars etc. We worked very closely with Zed providing them books from South Asia: whatever we published, they took in.

JKS: All in English?

UB: Yes, in English. We were publishing in English and a little bit in Hindi, but we had no competence in the other Indian languages. So our way to getting around that was to translate.

On literary gymnastics while translating A Rag Doll After My Heart

JKS: Talking about translation, Shruti, when we translate from one language to another, is meaning lost from the original or can we say another layer of meaning gets added to the text?

Shruti Nargundkar (SK): Well, this was my first attempt at translating and I just started taking baby steps and I didn’t even have an English into Marathi or a Marathi into English bilingual dictionary. So the first thing I did was to get a dictionary because, I wanted the translation to be as close as possible. But having said this, at times I haven’t found the exact word, the right word. So, I tried to say it with the addition of a few more words and do some sort of literary gymnastics with the word. Or I have just kept the original Marathi word and then given a little footnote with an explanation, or I’ve created new words, new logisms.

JKS: Fantastic, that’s great. Urvashi, do you have a response to that?

UB: Yes, I think the translator’s anxiety of whether or not she has captured the exact meaning of what the original intended is not the publisher’s anxiety, because the translated book is a new and transcreated product – it has to stand on its own. And I think, particularly in India, many people who pick up a book in English will probably know the original language, and they’ll then say, ‘Does it measure up to the original?’ But that’s really not the point. Does it measure up to itself? That’s what we need to ask.

SN: And in this particular instance I had an almost suicidal kind of death wish in – I didn’t know what I was going in for when I decided to translate a poetic novella, because the form posed so many challenges: to capture the sense, to capture the spirit and then to still keep it in a poetic form; tell a story but not make it very abstract, yet keep it poetic was very tough.

JKS: Because in a sense it is also a creation, is it not? You’ve taken up the onus of creating it: it wasn’t here before, and now it’s an actual thing.

SN: Yes, exactly. An analogy came to me in the morning when I picked Urvashi up from the airport, and I’ll use it here. The novella is about a woman’s journey with her adopted child and how she creates her own doll, it’s an allegorical reference to the daughter, and how they move through all the twists and turns that the story takes and finally there is a sort of denouement at the end. And for me it was the same, that’s what I was doing. I adopted the work and then I wanted it to be mine, you know. ‘This is mine, this is mine.’ (laughs)

UB: Yes, and then she got lots of funny comments from us…

SN: Yes, but that’s to be expected in the process. I mean I looked at it and sometimes I could see Urvashi literally wincing and saying, ‘Uhh… this is tacky!’ But look, sometimes you don’t know whether what you’re saying, apart from the fact that all the writers have this self doubt, is good or bad or tacky or beautiful. So like a little schoolgirl, I felt happy when the proofreader said, ‘very good!’

I said to myself, ‘No, I’m not writing it just for myself and I must defer to the wisdom of the reader out there…’

I mean, look my first and foremost thought was, ‘I must take this as a compliment from Urvashi or from any publisher who has taken the pains to make these comments’. That means that they have read it and they are invested in it as well.

What is this off-the-wall thing?

JKS: Coming back to challenges, Urvashi what were some of yours when you started Kali in the mid-eighties?

UB: See in some ways, when you are young and take on a challenge like that, the excitement of doing something that you love is so heady, that you don’t get defeated by the challenges. I think both Ritu and I have not been happier than when we were starting and I remember on occasions when we would be going from place to place meeting people, and saying to each other, ‘Look we are so happy, it’s so nice. Whatever’s happening is so wonderful,’ But there were lots of challenges. We had no money, so that was a big challenge. I mean we didn’t pay ourselves anything. So this meant finding money to live on.

Ritu had her husband, who is an architect and she had a home. I had my own place to live in but really I had no money, but then I had very modest needs, I didn’t want to live off my parents. So somehow managed from writing, my teaching job, doing this that and the other in the early days. The other challenge was to get people to take us seriously. With feminist publishing people thought, ‘What is this off-the-wall thing?’ ‘What are these women doing?’ We worked with printers, with binders, with typesetters – totally a male establishment.

Now the advantage was that both of us had worked in publishing for a while, so we knew these people and they knew us. But they still treated us like girls. So, it was difficult to get them to take us seriously, but they did only because we had a professional background there. There was no real opposition as such, but a big obstacle was indifference and a little bit of scepticism. Nobody stopped us from doing what we wanted, they just thought we were nuts. And then we did one book, and another, and another, and then there was this grudging admiration, ‘Oh! They are doing something?!’ Then we sold those books abroad and by the time we were in year four or five, people suddenly sat up and said, ‘My goodness, there is a market there, we didn’t even think about it’.

And then began another challenge, when the big guns started to swoop in with more money, more resources. Holding on to your authors was a challenge. Not giving in to despair because your authors went away from you, for all the right reasons because they need money, exposure, the whole works. I remember in the early days it used to infuriate me. And then it took me a while to understand that and realise that this is in the nature of things and the whole point is that if people are moving to bigger publishers who are publishing women, basically you are achieving what you set out to, and your task is always look for new material.

So the moment your thoughts turn that way, everything becomes exciting again. Throughout I think the one constant, and to me really the most important thing was the support of women activists in the movement. In the early days, we were the voice of the movement, there was a slightly troubled relationship because people expected that we would publish everything that everybody wrote, but we wanted to exercise some standard so that things could get into the market. And women understood that eventually. What would happen is that they would go into bookshops and ask, ‘When is the next Kali book coming out?’ So the booksellers said to us, ‘We don’t understand what’s happening? Nobody’s ever come to us and asked for books by a publisher’. But they were doing that, because they would just buy our books. They wanted to have everything!

Changing the “textbook culture”

UB: The Indian publishing industry was very different at that time. The market was dominated 80% by textbooks; the general book market, which is what we were addressing hardly existed, there were very few bookshops and mostly with foreign books, but it began to change. We were one of the first people who started that change. Now of course it’s very different. General books have made a space for themselves. But at that time finding a niche was difficult.

JKS: So was it all fiction, or nonfiction?

UB: No, it was nonfiction as well. And in fact one of the other big challenges was getting women to write. It’s like women have things to say, but if nobody’s paid any attention to them, they think, ‘Well what we have to say is not important’. So the task of making women feel self-confident about writing was a major task. Working with them and saying, ‘But you know you’ve got something in there, sit down and write it’.

This book that I mentioned to you, ‘The History of Doing’, I had decided who I was going to ask to write it, she was one of the activists in the movement and a very good writer. It wasn’t that she didn’t have confidence in herself, but she led a different life, she was heavily into drugs at that time and was leading an indolent life. I used to pitch up at her house every morning with my thick board and say, ‘Ok now wake up! You are going to write the next chapter!’ It was a bit like that. So that made it interesting and exciting, but also challenging.

JKS: Of course, that must have been challenging. That relationship between a writer and a publisher is quite fraught.

UB: Yes, it is. Especially if they are your friends it gets trickier. I remember another one of our classics. The book was all ready and the introduction was to be written, but the two editors simply could not get down to writing it. So I locked them up in my flat for about five days, and I had one of those early computers called an Amstrad, and I said to them, ‘Write.’ And I babysat the son of one of them. I hated the babysitting, but I did it. I was thinking, ‘I’m the publisher, what am I doing?’ But yes, they wrote a brilliant book and we still reprint it every year.

On structuring interview material

JKS: I know you’ve written and talked about the Partition for your book The Other Side of Silence, which is based on 70+ interviews with Partition survivors. How was that like? What was your process?

UB: You know my approach was completely random. Since I’m not an academic, a historian, a sociologist or an anthropologist I’m not constrained by any discipline. So it was just a general interest of mine and I started by talking to my own family. That was both difficult and easy because my mother had never really spoken openly.

Previous to that I had worked with a group of filmmakers making a film on Partition and they had said to me to help with the research. So I had to go to Amritsar and places and find survivors for them. I developed these strange kind of antennae, so what I would do is every time I would see somebody who looked the right age I would walk up to them and ask, ‘Where are you from?’ And I found that people who were Partition survivors had a way of answering that question with another question. They would always say:”Hooney ya picchey?” (Now or previously?) The moment they said that, I knew “picchey” meant pre-partition.

So, the way of starting conversation basically was to ask them where they were from, tell them what you are doing. I have to say it didn’t come that easy because in the beginning when I started seriously doing the interviews, I would tell lies to people. I would never tell them what I was doing and I began to feel very burdened with the stories because they were stories of such terrible grief. And at one point I thought, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I did three interviews in a day and I thought, ‘this is crazy’.

Then a very dear friend called Sudesh Vaid, joined me. For about two years, we did the interviews together and it was wonderful because we could both laugh about them afterwards. We would go off and have tandoori roti and daal and just talk, so it took the tension off. But Sudesh told me, when we started working together, she said, ‘Why are you lying? Why do you tell one story to one, one story to another? Be truthful and say what you are doing and give them a chance to accept or reject.’ That was a very valuable lesson, because then I started to tell people and they could choose whether they wanted to talk to me or not. I felt much better about it.

JKS: It’s a harrowing process to listen to somebody’s tragic story because it’s not fiction. It’s the truth. So how did you sift through your material then? Did you have a plan at the back of your head on how you would organise it?

UB: You know it’s damn tough. I had no agenda at the back of my head. But I knew that I would transcribe every single interview myself. So I lived with that material, and listened to it, I translated it, I taped it, I read it back and so on, and it began to dictate its own themes. I had really no idea how to use the material, so initially what I had done was I wrote up some stuff and I put all the interviews at the end and then I showed them to my publisher. He came back to me and said, ‘Look you are doing these people an injustice. Because imagine yourself reading the interviews, by the time you’ve read interview three you’ll be indifferent to everything that people are saying because it will start to sound alike.’ You can’t do that, he said. And asked me to think of a way of integrating some of the interviews into the chapters.

So I thought and eventually it came to me that the chapters were each structured around one particular theme. So I had a chapter on my uncle, who had stayed behind in Pakistan, become a Muslim and my mother never saw him again until 40 years later. I called the chapter Blood because it was all about blood relationships and how they were broken up. Then I had a chapter on women and another on honour, and how families killed their own women. And then I looked for interviews: one interview that would substantiate one chapter, not necessarily repeating the theme, but somehow complement it and that’s how I managed to structure the material.

On working on A Rag Doll After My Heart

JKS: Talking about process, Shruti could you talk about A Rag Doll After My Heart? Was writing it always on your mind?

SN: Well I did want to write, especially because of the choice I made. The choice for the education that I got, but my father wanted me to be a doctor. Especially after he had a heart attack, when I was in my years of reckoning: year 11 and 12. He said, ‘Oh these doctors have looked after me so brilliantly, I want you to become a doctor.’ Well, I have an interest in medicine, and I’m my family’s quack. But no. I have this physiological reaction to blood: I faint.

So I made that choice and disappointed my dad, although he was equally proud of me eventually. So by training and by choice I was on my way there. But I think it became more obvious later. It was only when I started teaching English as a second language that I started looking at the process of writing and that was the time I started thinking, ‘that’s good, I must write.’

And in this particular case, A Rag Doll After My Heart, which is a translation of Anuradha Vaidya’s poetic novella, (she happens to be my maternal aunt, my massi) it was there in the family. Every time she published a book, a novel or a book of short stories or whatever, we would read them. And she’s a prolific writer. So, when I read this book I said, ‘Oh! I wish I had written something like this’. And then I thought, I can translate this. But, it took a while for me to get down to doing it. I started and more than halfway, I went back and changed a whole lot of things, so I had to stop it.

JKS: And how many years was this?

SN: Ten years of a break in between. And after those ten years, when I thought I’d have the time to do it – I was not the same person. And the material was on a floppy disk, and I had to go to some lengths to get it transformed. So I had to get it on a USB stick to read it. I was in a process of grieving at the time. The business that my husband and I had started, it was our lovechild, and we had given it everything we had. We had taken very huge risks, and after we sold it, there was a sense of emptiness and grief.

The translation work came to my rescue and made me think about myself: am I the same person, am I going to look at it with a different point of view? But it all worked out because I had to go back, I wrote quite a bit of it and then two years since I started, Urvashi’s team decided to publish it. From the time I finished it to the time I signed up with Zubaan it was 6 months, and then there was a bit of time gap and when they edited it and sent the suggestions. Now when I read the manuscript, those suggestions were all for the good. That whole process has been a growing up for me.

On working with nonfiction

JKS: I can imagine that. So, Urvashi I know that you do a lot of nonfiction writing, so I’m just wondering if it’s the element of truth that draws you towards it more than fiction?

UB: No, actually interesting you say that. I think it probably is, in a sense. I know it from the negative, by that I mean I’m not attracted by the element of the imagination, if you like. And you need to have that to create fiction. I don’t think I have the capability to create character, plot and all of those things. I’ve never tried it, but this is what I instinctively feel. Having said that, it is the element of truth in nonfiction writing that draws me. I love people, I like to observe things, I like to internalise things and I like to write about them.

But when I wrote my Partition book, the Times of India did an interview with me and the journalist called me up and said, ‘Ma’am is this the first novel you have written?’ And I said, ‘It’s not a novel.’ Then I thought about it, because the style is a novelistic, storytelling style. I don’t make my characters speak in the way that many nonfiction writers today do, like Catherine Boo does that and I find that problematic. I don’t put words in their mouths. So in that sense, they are saying what they are saying and it’s a truthful representation as much as it can be transformed from orality to the printed word. But the story is told in a novelistic way, so I guess I have an interest in storytelling a bit like creative nonfiction. It’s the other stuff that doesn’t really attract me – the ‘what if?’

On publishing women’s writing in contemporary India

JKS: Lastly, what is the state of publishing women’s writing in India?

UB: I think it’s a good moment for women’s writing in India. I think many publishers are very open to women’s writing. In 2000, Ritu and I split and Kali split too, we each set up an independent imprint, we are now between us publishing twice the number we were publishing earlier (as Kali). There are other publishers who are doing stuff. So in that sense it is a good moment.

But in another sense, the mainstream publishers are only interested in mainstream women’s writing so they pick up the most obvious stuff: written in English, written by city women. For publishers like us the challenge remains how to go beyond that and how to be inclusive and diverse. You can’t do that by remaining confined to urban areas, by doing only English and so on. So we try to move beyond that, but it’s not so easy. Those voices get published, but not as much as they should, and they don’t sell as much as they should, unless there’s sensation attached with it.

JKS: Well, it’s been lovely talking to you – Thank you for your time Urvashi and Shruti, you have been very generous.