By Arjun Rajkhowa

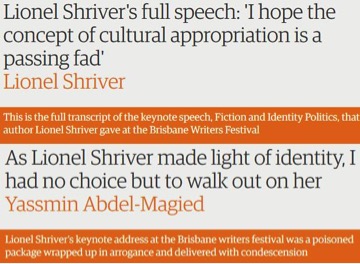

American writer Lionel Shriver recently delivered a keynote speech at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival where she discussed cultural appropriation, authorial autonomy, social expectations around works of art and a host of other subjects that have arguably been at the forefront of much critical debate in recent times.

Her speech provoked a lot of debate, as well as the usual outrage, grandstanding and squabbling on Twitter. I read the speech as well as some responses to it, and also listened to a discussion about it on the radio. I thought the speech raised many valid questions and argued convincingly against certain contemporary trends in the socio-cultural field. In this blog post, using Shriver’s speech as a point of departure, I want to discuss four distinct ideas or areas of concern that I think are pertinent to the conversation at hand.

Authorial voice

Shriver’s speech, at its core, was about authorial autonomy. However, from what I can gather, most people’s responses and reactions to her speech have been predicated on what may be characterised as the concept of authorial responsibility. Authorial responsibility is a relatively new concept.

A traditional understanding of the creative arts would perhaps privilege the former over the latter, but the zeitgeist seems to place responsibility and care where freedom and autonomy would have previously been. This is especially so in respect of the critical-commentary work that creatives habitually engage in outside of their creative endeavours. At conferences, seminars and talks, for example, the creative is scrutinised and assessed by a set of amorphous but easily recognisable criteria that valorise and emphasise goodness rather than critical rigour.

A new schema has emerged that circumscribes the artist’s social-critical voice within predetermined bounds. In this schema, the author is expected, above all, to offer commentary that is responsible and socially beneficial. Iconoclasm – that quaint concept that Shriver invoked in her speech – is looked upon unfavourably or with mild amusement. Any diffidence, rebelliousness and irreverence on the part of the artist can be dismissed as self-indulgence and arrogance, rather than recognised as an expression of genuine discomfort with the social consensus. Provocation is passé.

A key feature of Shriver’s speech that provoked much outrage was its emphasis on the author’s proprietorial autonomy. An author/artist can do with their creation and their creatures, so to speak, exactly what they’d like to do, Shriver averred. This truism – an assertion of an unquestionable truth about the creative process – provoked outrage because it was seen as evincing ‘arrogance’, ‘entitlement’ and even ‘colonialist’ attitudes.

Therefore, it can be argued that what we are witnessing – and perhaps this is not entirely unexpected when a particular art form goes into decline – is an intellectual push towards the disavowal of the agency of the author, and its replacement with bland conformity. Shriver makes this point succinctly: not only is it difficult today to do and be sustained by writing as a vocation, you must also constantly grapple with internal misgivings about and external pressures on your agency as a writer. These may not always be apparent or obvious but they are indeed often palpable, further etiolating or rendering toothless what Shriver characterised as the most irreverent of vocations (or avocations).

American hegemony

So-called American liberals have for a long time now been dictating the terms of cultural engagement for the rest of the world. This is especially true when it comes to how people think about the concept of cultural appropriation. It is not so much that we are told what the correct thing to believe and espouse is. Instead, the actions and manoeuvres of so-called liberal students and sundry others demonstrate to us the limits of our engagement.

Certain things are verboten, and we know this not because someone or some movement came out with a cognisable set of rules, but because hostility, skepticism and purblind censorious rage hounded those who did not abide by these unspoken rules. Shriver’s speech refers to one illuminating essay, written by a so-called ‘liberal professor’ who used the pseudonym ‘Edward Schlosser’, that highlights this but any number of such essays documenting the rise of liberal intolerance (I am almost tempted to write ‘tolerant intolerance’) can be found online.

It is the act of protesting and making impossible certain thoughts, acts, works, practices and what-have-you that eventually determines what people understand and think when the accusation of cultural appropriation is invoked. As most of these protests and acts of proscription take place in the US, this newly re-inflected concept of cultural appropriation embodies and perpetuates American hegemony in the intellectual arena. And make no mistake, in many instances in the US (again, relevant references may be found in Shriver’s speech and elsewhere), when protesters and proscribers accuse someone of cultural appropriation, it is an accusation rather than a criticism – the intention is to demonstrate the accused’s venality rather than debate their judgment.

American sentiments, American race relations and American problems suffuse and overwhelm all conversations about cultural appropriation, rendering this concept a peculiarly and quintessentially American export. The rise of cultural appropriation as a tool of protest and analysis marks the coalescence of a range of phenomena that cannot be summarised or delineated in a short blog post, but it also most definitively signals continuing American hegemony in the field of ideas.

The concept of harm

Harm is an idea that is very much at the centre of many recent debates relating to culture, education and a host of other areas, and it is one that I find most difficult to grapple with. The idea of harm that pervades literary and artistic debates is perhaps its most nebulous version. To me, the claim that someone has been harmed by a work of art is a contentious claim – it is not one that should expect to go unquestioned. It is not one that should go uncontested.

Harm is a concept that has decidedly serious connotations, and when it is used to characterise the effect a work of art has on someone, or, even more problematically, a whole group, it should be used with caution rather than reckless abandon. Taking a concept that is intrinsically objective and verifiable, and rendering it nebulous and unverifiable, and then using this against creatives, is not something that I consider particularly laudable.

Speaking back to history

The rage against cultural appropriation can be seen as rage against colonialism and western hegemony. It is an expression of anger about historical injustices – anger that, perhaps for the first time in history, can demonstrably shape the cultural or artistic practices that are perceived as being intertwined with those historic injustices, and make these accountable. This is the only point on which I am in agreement with the proponents of the concept of cultural appropriation. The charge of cultural appropriation belies long-held animosity and resentment at racism, conquest, dispossession, theft, loss, misrepresentation and several other phenomena.

However, I am almost reluctant to characterise it as ‘long-held’ resentment, because this animosity is not really something that transcends generations – anger about cultural appropriation is as much a culturally- and temporally-specific phenomenon as it is one that can be said to transcend time. While anger against injustice may transcend generations, this particular manifestation of the anger that we now see before us, pervading protests about costumes, songs and the occasional yoga studio in the US, is something that emerges from the specificities of the wider contemporary socio-political conjuncture.

On one level, it is an anger that is empowered with the means of affecting outcomes, and is thus perhaps more virulent than anything authors, artists, musicians and other creative practitioners have encountered before from their intended audiences. On another, more fundamental, level, it is an anger that feeds into the zeitgeist underlying contemporary policies, norms and practices around recognition of historical injustice. In that respect, the charge of cultural appropriation is one that is altogether appropriate.

However, my gripe is that I believe the targets are poorly chosen and, in many cases, the manner of protest (again, protest, and not just criticism) is just plain ridiculous. Overzealous American millennials with inflated egos have turned a conversation about history into a shouting-match replete with foul histrionics. They have taken what is still in large part a conversation about historical injustices as well as historical ebbs and flows, and turned it into a farce with disturbing authoritarian undertones. There are many who deride criticism of these antics as something akin to hyperbole – ‘You are exaggerating!’ – but the truth is, you don’t need to exaggerate the transparent unfairness of the many recent instances in which cultural appropriation has featured as the central crime.

Question the criticism

There is now a tendency to countenance the excoriation of certain works of art or the maligning of the intentions of certain authors as ‘legitimate criticism’. However, as noted in Shriver’s speech, in the US, the heartland of all culture wars, the line between de facto proscription and criticism is one that is constantly shifting, and the arts are hardly immune to these shifts. In such instances, ‘criticism’ belies far less legitimate tendencies.

But putting these aside, questions need to be raised even about the validity of such criticism. Debates need to occur that are free of moral posturing, grandstanding and, worst of all, reckless mudslinging about the intentions and character of authors, creatives, critics and others.

Arjun Rajkhowa works in tertiary education in Melbourne. His research interests include media, human rights in Asia, postcolonial politics, literature and popular culture, and gender and sexuality. He has written for academic journals and for online media outlets such as The Conversation, Kafila, The Hoot, Peril, Overland, Words Apart and Scribbler.co. He has been a volunteer radio programmer for community radio in Melbourne for over three years.