By Meeta Chatterjee-Padmanabhan

While rearranging book shelves at home, I came across old notebooks with Hindi and Tamil alphabets in my children’s handwriting. Each carefully formed letter triggered memories. I remember the smug satisfaction that my husband and I felt as we helped our girls connect with their heritage languages. The girls, on the other hand, barely suppressed their annoyance at not being able to join their friends leaping around with water guns in their hands and screaming with delight just outside our door. Many years later, reading Sticks and stones and such like, Sunil Badami’s phrase ‘the awkwardly knotted hyphen’ that inscribes the uneasy yoking of two distinct national cultures: ‘Indian-Australian, Australian-Indian depending on the day’ intrigued me. I have wondered, how awkwardly knotted can a hyphen be before it stops being a hyphen?

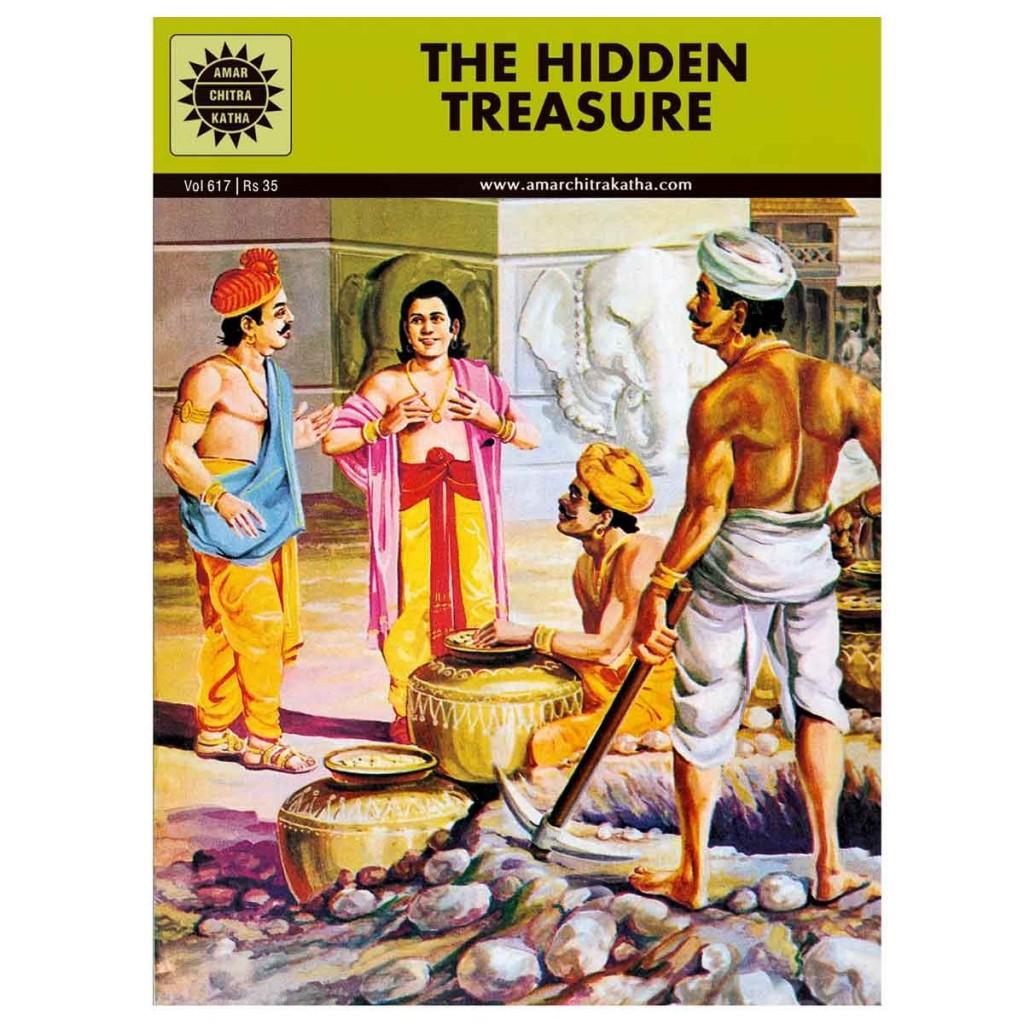

As a first generation migrant and mother, I desperately wanted my children to stay connected to their ‘home’ culture. On every visit to India, we were harangued about the dangers of the loss of culture and language by relatives, neighbours and neighbours-in-law. Even strangers we met in trains gave us Amar Chitra Kathas so that our girls would know about Indian culture. In our anxiety to preserve Indian traditions, we recreated our homes here in Australia to resemble the ones we have left behind.

My husband and I morphed into parsimonious creatures to save enough money to take our children back ‘home’ every year or two, so that they could experience the skin-to-skin contact with their kin and live and breathe the culture of our ‘native’ places. We attended family celebrations whenever we could. Once there, the train journeys were opportunities to imbibe the heavenly and the horrendous sights and smells of the Indian landscapes while reading Paul Jennings’ ‘Round the Twist’. The spontaneous friendships and the great Indian card games were an added bonus.

I plead guilty of ‘ruining lives’ (words of my six year old daughter from an eavesdropped conversation). My husband and I come from different parts of India, so there was no common Indian language spoken at home and to complicate matters, our Indian friends spoke other Indian languages. Therefore, goading our children to uncover the intricate honorifics in Tamil or the morphology of plurals in Hindi without exposure the languages was unfair. I now understand this.

But on those long hours in summer when my children’s friends were busy climbing mulberry trees or chilling by the pool sucking on icy poles, my girls were learning other languages with tears in their eyes. ‘Ped ke pechey panchi chupa hai’, ‘There is a bird hidden behind the tree’ is etched in their memories. The sad part is, never has a situation presented itself where they could use the sentence without sounding slightly deranged.

While their friends dated, we dragged our girls to Bollywood films. Om Shanti Om, particularly, sticks in mind. The long film left them baffled. The bizarre plots and the even weirder dance routines shocked them. Luckily, they did not see Bollywood as a way of connecting to India. I am grateful for this. There were exceptions though. For an entire summer, the water gun-trotting brigade of our neighbourhood gave up their rampage across front lawns to dance to A.R Rahman’s tunes, Hoja Rangeela re. The season culminated in a concert at home where our delightful brigade danced to songs whose meanings were irrelevant for them. Spider drinks and fairy bread kept them appropriately hyperactive through their performance.

My girls understood in-betweeness in a visceral way. Having to straddle two cultures, one at home and one outside made them pretty adept at coping with the unease of blending. So, they got Bend it like Beckham. The plight of the Sikh girl in Hounslow who wanted to play football instead of learning to make ‘the full Punjabi dinner’ was understandable. The hilarious rebellion of the teenagers in East is East stayed with them for a long time. The story of Gogol in The Namesake made a strong impact.

Fifteen years on, things have changed. The girls have moved out. They are now writing and performing their hybridity in their own ways. Their visits to India are no longer educational trips. There are lasting ties between cousins forged through Facebook and cheap flights. Family dinners may soon begin to resemble small scale UN meetings. Our yearning for the ‘home’ is less intense. Relatives have released us from homilies about preservation of culture as they watch India change before their eyes. How to apply for PR is a greater concern.

In writing this blog, I am conscious that I have conveniently glossed over tensions and complexities of the hyphenated experiences of my children and conflated the experiences of one child with that of the other for writerly economy. There are glaring omissions in my recollections. For us too, the hyphen is awkwardly knotted, but perhaps, the malleable and ductile hyphen is configured differently.

Image source: Amar Chitra Katha